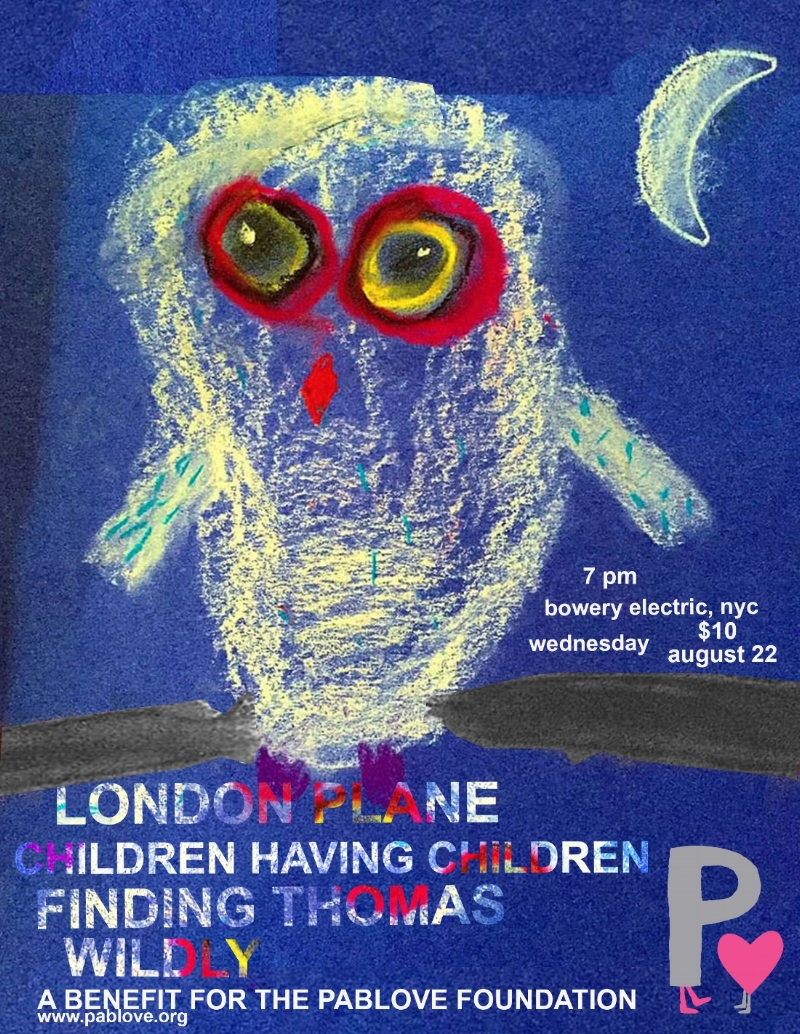

CHC EP ANNIVERSARY (PART I)

by STEVEN KAISER (Piano, Guitar, Keyboards, Vocals, Production)

photo by Matthew Fugel

***

"Hey babe."

I don't need to bother checking the caller ID on the studio phone, as the night manager Jeff is definitely the only person who has addressed me as "babe" since I started working at Southern Tracks Recording and given up any attempt at dating. Though I'm not officially working on this particular Sunday afternoon, I basically live at the studio and can be found there anytime I'm not rehearsing or in class. I am using this rare downtime when the studio isn't booked to mix a song called "Film" that my band recorded there earlier the same month. It will be the opening track on our self-titled debut EP.

"I'm in my car with Peter Buck, and we're thinking of swinging by the studio. You gonna be there for a little while?"

photo by Matthew Fugel

My imagination immediately runs wild. I envision the legendary Peter Buck of R.E.M., a personal hero of mine, walking into the control room and politely asking to hear the song that I have pulled up on the console. He will be so blown away by the quality of the songwriting and the unique brilliance of the production that he will excuse himself and immediately call all of his clout-wielding industry contacts. By day's end my band will have a manager, a booking agent, and a record deal on an indie subsidiary of a major label. The deal's terms are surprisingly generous, considering that they allow us to maintain total artistic control and retention of our masters.

"Hey babe, you still there?"

In addition to being the night manager, Jeff Calder is also the frontman of alternative rock pioneers The Swimming Pool Q's. He has become a close confidante and we spend hundreds (possibly thousands?) of hours in conversation during my internship-turned-job at the studio. For all our differences in taste, we're kindred spirits who love literature, rock, and the twisted relationship the two occasionally share. He seems to know every musician in Georgia and is a walking encyclopedia when it comes to… well, most things. He even has a "thank you" on Siamese Dream for lending the Pumpkins a bright pink six-string bass during their recording sessions. (He lets me play it when I ask him to bring it in.)

I snap out of it, ask Jeff how he's doing, apologize for my daydreaming, and tell him I'll be around until late that evening. Though he sounds very casual, his relaxed tone is probably intended more for his passenger Peter than it is for me. He knows that I'm a ravenous R.E.M. fan. Jeff and I work at what is indisputably one of the premiere studios in the world, Southern Tracks in Atlanta.

Nearly all of the studio's projects are helmed by legendary producer Brendan O'Brien, our unofficial in-house client. The walls of the studio are covered floor to ceiling with plaques of the multi-platinum albums he's made with Pearl Jam, Rage Against The Machine, Bruce Springsteen, Stone Temple Pilots… the list goes on and on. Though I have gotten used to meeting and working with full-fledged rock stars (including The Boss) on a regular basis, I'm less concerned with Peter Buck’s rock stardom than with the brilliance of the music he's written, the soul of his guitar playing, and the glimmering hope that he'll recognize a bit of that same magic in our music if he were to hear what my band has committed to tape.

The hours roll by quickly in this windowless room, as they often do, and I finally print a mix that I feel pretty good about. I then print another mix pass with the vocals up one decibel, one more with the bass up two decibels, plus an instrumental version and finally an a capella version. In my time at Southern Tracks, I've learned the process by which the professionals handle such matters, though I don't have anywhere near the engineering abilities to achieve the sounds in my heart and mind.

By the time I activate the security alarm and walk out the front door, it's 2:00 in the morning. Jeff will tell me the next day that Peter changed his mind and decided to grab a bite to eat instead.

***

Our band name is chosen right before we finalize the cover of the EP. We have decided to scrap our previous names, most recently The Audience (because we found out it was already in use) and prior to that The Jaws Of LIfe (because everyone besides me hated it). The runner up in our final vote is Think In English, a lyric from a strange new tune I am in the process of writing. The winner is Children Having Children, taken from a lyric to an "outtake" of the EP that remains unreleased although I'm quite fond of the song.

photo by Ali Kesner

It's worth noting that I had jotted this lyric down on a piece of paper during a quiet evening behind the register at the bookstore where I worked, but then emptied my pockets when I got home and threw the piece of paper in my bathroom trash can.

My girlfriend at the time saw "We are children having children" staring up at her the next day from a scrap in the bin and asked me what it meant, thus saving the lyric for posterity in the form of our band name (and in the bridge of an unreleased song about a miserable infidelity-fueled breakup with said girlfriend shortly thereafter).

***

In the short window of time between the release of the EP and my move to New York, I find myself standing behind a theater in Athens. Not the city in Greece that's known for being the cradle of Western civilization, but the one in Georgia that's known for being the city where I got drunk for the first time, where I got high for the first time, and also for R.E.M. (I still haven't met Peter Buck to this day although I made uncomfortable eye contact with Michael Stipe at a Yeah Yeah Yeahs show a few years after moving to New York).

I'm waiting with my friend Kara after a Smashing Pumpkins concert in the hopes of chatting with my two favorite musicians of all time, Billy Corgan and Jimmy Chamberlin. She and I have waited like this so many times in so many cities, and though we've met them both before, this is the first time I have something of my own to offer.

When Billy eventually comes out and greets the fans, he winds his way around the respectful circle and comes over to us. We congratulate him on a great show and I ask him if I could possibly give him an EP that I recorded. He immediately shakes his head and starts to tell me why he can't take other people's music/demos. I already know the reasons -- primarily the risk that a star of his stature is prone to lawsuits from people who might say, "I let him hear my demo and he ripped off my song."

photo by Ali Kesner

But as he's beginning to explain, he catches a glimpse of the cover and the band name.

"Children Having Children...hmm."

He takes the CD from me and gives it a closer look, followed by a quizzical but approving nod before thanking me and sticking the EP in his coat. Billy gives a quick wave to the stragglers that are still there before heading for the bus.

In that moment, not knowing whether Billy will ever play that CD or if it's headed straight for the bus trash bin, I am ecstatic. Partially because I've finally given a few tunes to the man who has given me so much music, but also because the only reason he took the CD from me was its beautiful cover -- a photograph by a close friend and an incredible artist, Ali Kesner.

The cover is a photograph of her younger brother Slater on the top of a ladder, high in the blue sky, staring at the top of a barren tree. When she first shows me the photo, I know that it is not only the perfect image for the EP but for the spirit of all the music I wanted to make with Children Having Children.

Though my relationship with Ali is complicated and convoluted during this period, the image is striking, vivid, clear. And unlike the recording itself which alternately makes me grin at our ambition and cringe at our execution, the cover image of our first EP still makes me unabashedly proud. It's a masterpiece.

On my drive back to Atlanta, I leave Ali a voicemail to tell her so and to let her know what transpired that night in Athens, the southern cradle of drunken underage dreams.

***

The studio owner Mike Clark initially turns me down for the internship because of my class schedule. He is matter-of-fact in his rejection and makes clear that he has more important things to deal with. Southern Tracks is the rock studio in Atlanta, and I know that an internship anywhere else will be a great disappointment. When I call Mike back two days later and tell him that I've convinced my department head to re-arrange the entire class schedule for all of the students in my program, Mike says just as matter-of-factly, "Great, I'll see you Monday."

Six months later, while we're eating lunch at a bar called -- I shit you not -- The Rusty Nail, Mike tells me and the three other members of our tiny staff that he couldn't believe the balls it took for me to fuck up everyone else's schedule just to land the internship for myself and how he'd had a hearty laugh about it as soon as he hung up the phone that day.

Starting on day two of my internship and every day thereafter, when Mike walks into the lobby, I am waiting with a piping hot coffee, light-and-sweet, in his favorite mug. We get along like peas and carrots although we are different in almost every way outside of our love for music and the people who make it. On an otherwise uneventful morning, Mike takes us out to a diner for breakfast and I make the mistake of ordering fruit crepes. He scowls at me and asks if I'm "some kind of socialist." This sums up our relationship pretty well.

I'm a student at the School of Music at Georgia State University, majoring in music technology and production. My primary intention is not to become a recording engineer or a producer for other people's music (though I’m certainly not opposed to the idea). I’m here because I want to learn how to record my own band's music. And when my professor recommends me to Mike for an internship, the doors seem to begin opening in front of me. Although I'm a good student and show some glimmer of promise as an engineer, Dr. Robert Scott Thompson and I share a love of Bowie, U2, Roxy Music, and The Kinks. These musical touchstones are what endear me to him from the get-go.

The studio internship strategy had paid great dividends for a number of my idols, like Trent Reznor of NIN and Royston Langdon of Spacehog, who both learned the ropes and recorded successful debut albums as a result. And I think something similar happened for Bon Jovi too. A few days before I start my internship, Dr. Thompson pulls me aside after class and subdues my expectations as he tells me, "Brendan O'Brien hates interns. Don't expect to talk to him let alone set foot in the control room for a few months."

As an uber-successful rock producer, Brendan O'Brien is a bit of an anomaly in the city of Atlanta at that time, which is primarily a hip-hop and R&B town when it comes to the studio scene. But it’s his hometown, his kids are growing up there, and he loves Southern Tracks — largely because of his relationship with Mike. While my professor isn't wrong about Brendan's high standards for the people in his work sphere (which I will come to affectionately know as "the pressure cooker"), he is dead wrong about the silent treatment.

On my first day, which is also the first day of a session for the new Train album, a man in his early 40s wearing jeans and sneakers, blonde with boyish good looks, runs out of the control room. He introduces himself with a friendly handshake and already knows my name.

"Hey, Steven? I'm Brendan. First day, right? Great. Listen, I need you to go to Guitar Center and buy some percussion shit. Whatever you think will sound cool."

He hands me his Amex and runs back to the control room. I guess I bring cool-enough shit back quickly enough, because I'm ingratiated with Brendan from that day forward. I also hit it off with Brendan's amazing engineer Nick DiDia ("You don't fuck up my food orders and you bring back the change, so I think you'll go far") and his editor Billy Bowers. Before long I'm sitting in on sessions. A little longer still and it feels like I'm part of the family. Many surreal moments. Too many to list here.

photo by David A. Palatsi

I don't talk about my own songs at the studio except with Jeff and occasionally our chief engineer Tom Tapley, who becomes the older brother I never had. Tom and I frequently spend 60-90 hours a week together, and though I'm essentially at his mercy, he is always kind, respectful, and even protective. It's not the time or place to chat up my creative side in front of Brendan or Nick, not yet, and I know that. But part of me wonders if perhaps I should be more open about my ultimate goal. Either way, I keep my head down and learn to do the job of assistant engineer as well as I possibly can while beginning to carve out a vision for how I can eventually work on my own music at Southern Tracks.

After everyone leaves the studio on a given night, I usually lock the front door and head back to the exquisite Yamaha grand piano, alone in the dark studio, to practice my Hanon fingering exercises and run through a few of my songs. This same piano appears on recordings I love by Ben Folds Five and Aimee Mann, among others, and it won Grammys for Springsteen and Train. This is the piano that I will play on our EP.

One night Brendan gets to his car before realizing thay he left his wallet in the control room. While I’m practicing, he walks back in and pokes his head in to tell me that I have to let people know what I'm capable of. He also calls me "Chopin" for the next few weeks. He is impressed by whatever he heard, which is a nice boost to my confidence, even though I can barely scrape by as a pianist and he's one of the best musicians I've ever met.

The collection of instruments and recording equipment at the studio is insane by all measures. The microphone collection is one of the best in the world. And not only is all of the gear great, but it's spilling over with history. When I've proven myself trustworthy and I finally do get a few days on the books to start recording the EP, we kick into high gear rehearsal mode. Although our initial dates are bumped back when Elton John calls to book the studio, our long weekend at the studio finally arrives and we take full advantage -- of everything.

David, Matthew, and our session drummers are all immediately struck by this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity in a studio we could never afford, using instruments we would normally be afraid to touch. Sure, from an engineering standpoint I barely know what I'm doing and I've never really sung in a vocal booth before, but...fuck it. (In hindsight, I'll begin to suspect how much Tom -- who has graciously offered to help us on his days off -- has probably improved the drum sounds while we were tracking to make sure I get something decent).

David and I tag-team the 19th century pump organ that was used on Pearl Jam's "Better Man". I record a pad-like series of tightly-voiced chords on a B3 organ that once belonged to Elvis. Mellotrons, hurdy-gurdies, vintage Ludwig & Gretsch drums abound. To say nothing of the guitars -- antique Martins, vintage Gibsons and Fenders worth more than I can allow myself to remember while I'm holding them. And access to every amplifier that's ever been worth playing. All feeding the 72-channel SSL console that has passed audio from so many hit records and has been a driving force in convincing Brendan to come back to Atlanta after his early success out in L.A.

It's a very special and exciting time in my life. One of the best. But I'm struggling. I sleep so little in the years I work at the studio that my body will spend the rest of my life catching up. What little sleep I get is frequently on a couch at Southern Tracks or the university studio basement. I am making $100 a week, and I would be burning through my savings if I left the studio often enough to spend any money. My diet is mostly reprehensible, except when we are in session, in which case I enjoy whatever Brendan or Nick buys for the band and the studio team. (Their generosity is one of many gestures that exemplify the class with which they carry their success, and I will model much of my behavior in and out of the studio for the rest of my life on what I learn by observing them.)

Though my band's first proper recording process is a genuine thrill, I'm succumbing to the weight of the course-load at school and the relentlessly intense environment at work. The studio demands a level of perfection and attentiveness that -- while appropriate given the projects we're working on -- I have never experienced before. Add to this my lack of any social life and the intense pressures I'm putting on myself to make a "definitive statement" with my band's first recording, and I crack a bit at key moments in my own recording sessions.

After our first long day of cutting six rhythm section tracks intended for the EP, I weigh the sheer number of overdubs ahead of us against the looming deadlines before melting down and basically giving up altogether in emotional paralysis. David is able to talk me down from the ledge after an hour or so -- a wasted hour -- so we can start banging out guitars and keyboards. These overdubs are the emotional highlight of the session, and the demands of rhythm section tracking are temporarily lifted as we get to experiment and explore.

Vocal recording is a multi-faceted crisis. My inexperience as both a singer and an engineer collide with the intense emotional content of the songs. When I'm not delivering the goods, which is most of the time, I either take it out on David as he operates the record button in the control room or I simply devolve into a tantrum of self-loathing in the booth as I'm unable to switch between the separate performer and producer sections of my brain.

When it comes time to mix, I'm so traumatized and ashamed from the vocal recording experience of the ten songs -- five on the EP and five that don't make the cut -- that I concentrate almost entirely on the instrumental tracks as I can no longer mentally process the vocals and fail to pick out the right takes or place them properly in the mix. This major flaw ultimately overshadows the many redeeming qualities of our debut EP and teaches me an unfortunate but valuable lesson. Though I walk away from our finished record with a sense of failure, a part of me understands that we have done the best we can and that we will carry many such lessons into future efforts.

One afternoon when Brendan's out in L.A. and the studio isn't booked, Mike Clark walks into the lobby and matter-of-factly tells Tom and I that he has been diagnosed with lung cancer. He barely touches his coffee. The fear in his eyes is palpable. He won't walk into that lobby again for several months, and when he does, he will be almost unrecognizable from the effects of his disease and the treatments to eradicate it. Transformed from a beardless Santa Claus into a pastel skeleton, his voice seemingly an octave higher, he will barely have the strength to hobble over to an office chair in this magnificent studio that he built well before I was born.

It gnaws on me during Mike's time away that I should drive out to visit him at his farm. I don't do well with illness, struggling with bedside small talk in the face of pending death, a sign of my own weakness of character. And though I almost call up his wife many times to see when it might be a convenient time for me to come visit, I never do.

Though things are supposedly looking positive for Mike's recovery at the time of his last trip to the studio, he will capitulate to a recurrence of his cancer a few months later and the studio will never be the same after his death despite the best efforts of those who understand its historical significance and have fallen under its inexplicable magic spell. Within ten years Southern Tracks will be sold for parts and abandoned.

***

I'm driving back from my then-girlfriend's apartment early one morning in my cherry-red Oldsmobile when I hear on the radio that Elliott Smith was found dead of an apparent suicide. The news catches me completely off-guard, and it’s the first time in my life that I’m learning of a hero’s death in real time. The relationship with my girlfriend is new, effortless, intense, loving in all the best ways. I can't remember ever feeling happier in my own life than I do in that moment. And meanwhile this incredible songwriter whose music helped me through tougher times was apparently at such a low point in his own life that he stabbed himself in the heart. When I get back to my apartment on the northern edge of Atlanta, I jot down a few stanzas in the ten minutes before I have to get back in the car and leave for my 9 a.m. music theory class.

photo by Stephanie Routier

Years later, with the girl long gone -- she left me for her English professor after a clumsily-hidden affair -- I'm sitting in the vocal booth at Southern Tracks after a particularly draining session. I begin to fingerpick my way through a progression on a parlor-size 1928 Martin acoustic and hum a series of melodies. This musical sketch sticks in my head for a few weeks before I decide to pair it with the lyrics I had written in reaction to Elliott's death. While David and Matthew don't really react to the song when I play it for them, I feel very strongly that I've found an exciting new direction for my writing.

It's straightforward and airtight, with a guitar part that's fairly difficult for the player (me) but deceptively simple for the listener. I hear a searing intensity within the quiet instrumentation, recoiled like a spring or, better yet, a rapid propulsion of music around an emotive nuclear core, threatening to detonate like an atom bomb if jostled. "Atomic rock," I say half-jokingly to the guys when I try to explain the idea.

In these early years of my songwriting, I put immense pressure on myself to push the boundaries of harmony and form as I understand them. Songs like "Museums", written in a practice room at the music school, point the way to where I think the band is headed. Though I continue to expand my songs in this direction of complexity, I simultaneously begin to accept that without a full-time touring band, these types of songs are nearly impossible to arrange and execute. This is the biggest time-suck at our sessions, as we ask drummers to understand arrangements that are incomprehensible to outside musicians.

My new song, an inner dialogue about the peaks and valleys of a life in the wake of Elliott’s death, marks a different direction altogether. The music is simpler in a way but uncompromising in my pursuit of an original voice. And though I will eventually find a way to merge the two approaches, I decide to record "The Morning News" with an equally dissimilar production approach to the bombastic roomy drums and stacks of overdubs on the other songs.

I limit myself to three instrumental lines -- displaying my newfound understanding and love of counterpoint -- to be performed using just one guitar and recorded with a single microphone in one tiny room at the school basement studio. The setup is simple enough that I can track all three parts on my own one night while waiting for David to arrive, and then I cut a few vocal takes on the same mic when he gets there.

The clock is ticking, as we have general admission tickets to see U2 at the arena a few blocks from school. We have decided in advance to leave the studio no later than 3 a.m. so we can camp out for a good spot on the arena floor. The track that will unexpectedly end up on our EP is basically finished that night.

When we get to the arena, the line is already hundreds of people long and stretches well around the building. These fans are bundled up, many wrapped in sleeping bags or dozing in lawn chairs. It's a very frigid November evening by southern standards. David and I take our spot in the back of the line, hang out for about ten minutes, exchange a few inquisitive glances, and then both enthusiastically agree to go back to our apartment for some much-needed sleep.

We drive back to get in line around 5 p.m. the next day, an hour before doors open. Our spot on the floor is more than adequate given our short wait, and the show is incredible. Though we don't say as much, U2’s performance is a welcome reminder that a few high school friends like us can throw together a band of non-musicians and transform the world with their songs. It helps David and I to justify the sleepless nights, the challenging rehearsals, and the hard hours we're putting in at the studio.

When she and I are temporarily on speaking terms again, my ex-girlfriend (who is not a U2 fan) will tell me that she had ended up at the same show with some friends. On their way home, they got stuck in traffic directly behind my car the entire way home and she was terrified that I would see her in my rear view mirror. Lucky for her, I was all eyes ahead. And even she had to admit that the show had been spectacular.

***

At some point -- I don't remember exactly when -- I decide that the "band" has to move to New York, the city where I was born and the place I've wanted to get back to for as long as I can remember. The opportunity at Southern Tracks delays the move by at least a year but the itch remains.

We still have no drummer, and resign ourselves to scheduling two session drummers for the recording of our EP: Nathan Lathouse (who rejected an offer to join the band after his audition) and Adam Bailey (who I never played music with or even met prior to the session). Between our inability to find the right permanent drummer and a lack of any perceived “scene” that we can infiltrate, I am able to convince our bassist and co-founder David Palatsi that we should get the fuck out of Atlanta

photo by Matthew Fugel

We've lost a few band members in the years prior, including our cellist Evan Robertson and guitarist Tanner Smith. Through the rehearsals leading up to and during the recording of the EP, the band has been a tight-knit trio: myself, David, and our new guitarist Matthew Fugel who -- despite being a better singer than David and I put together -- is willing to take on the role of lead guitarist while I continue singing and playing piano on most songs. The three of us move into an apartment together. Matthew and I even take an impromptu trip to Paris, sharing a bed in a hostel to save some cash.

I've written almost all of the guitar parts before Matthew joins the band, and though my "chops" as a guitarist are unimpressive, I can be fairly brutal in my relentless pursuit of what I consider to be the right notes and the right way to play them in order to serve the song. And since I haven't heard enough evidence that Matthew has found his own true "voice" in his guitar playing, I'm basically asking Matthew to play the parts exactly the way I would play them. All while knowing that I would be the guitarist in the band if we had been able to find a keyboard player.

There are some guitar-related struggles at both rehearsal and in the studio. This inevitably spills over into home life, though I have infinite respect for Matthew as a human being. He's astute, compassionate, a jack-of-all-trades and master-of-most-of-them. And I can see he's working his ass off to play beyond his ability, which is already leaps and bounds above his skill level before joining the band.

Whether or not we even invite Matthew to move to New York is hazy to me now, but once the EP is complete, it becomes clear that he won't be continuing on with us. Given my own frustrations with the final product and the knowledge that Matthew will be staying in Atlanta, I decide that for the purpose of our image/brand as we begin promoting the EP, the band is now a duo consisting of just David and me. Though I know it's unfair and though David tries to talk me out of it, I still decide to reflect this lineup change in the liner notes even though Matthew has worn so many hats and put so much sweat into the EP.

This would be even lousier if any listeners had given a shit about the music on the EP let alone its liner notes, but I still strongly regret this decision as it reflected my pettiness and selfishness in what felt at the time like a necessary sacrifice for the good of my grand artistic pursuits. A pointless slight to a good friend ultimately undercut what was worthwhile about the EP, which was the generosity of Matthew, David, and the others who tried to help me realize those pursuits and offer their own musical vision to the process.

Flash forward to 18 months later in Brooklyn and our co-habitation of a sink-less, curtains-for-walls one-bedroom railroad apartment where I comically live "in the closet." David has also had enough of my "vision." We've been through thick and thin since high school, learning to make music together and developing a common musical language that makes little sense to anyone outside our bubble. But he misses his girlfriend back in Atlanta and he's going insane listening to me practice scales on the other side of a piece of fabric. More importantly, our musical connection is fading and this friction starts to overshadow our friendship.

He moves back home, salvaging our friendship but dashing my dreams for a full band (despite the fact that I finally meet a killer keyboard player named Face Yu). Children Having Children essentially becomes a home studio recording project of mine until David introduces me to a drummer named Matt Lauritsen in 2016 and I head into the studio once again with the same burning desire that I felt a decade earlier. This time I let a real engineer named Bob Mallory handle the console. David, my closest friend, attends these recording sessions to take photos and begins to re-define the image of our band with his camera.

A few months later at David's wedding on a Mexican beach, my pages get caught in the wind and blow away in the middle of my best-man speech. Matthew is standing a few feet to my right and intercepts them before they are lost to the ocean forever. He returns the pages discreetly to my hand so that I can finish whatever it is I’m trying to say.

***